The generation of listening files begins with a digital description of the space, including the acoustically significant room surfaces, as well as estimates of the sound absorption and scatter characteristics of these surfaces. For either existing or prospective spaces architectural CAD drawings are ideally available, greatly simplifying the data capture process. The captured data is then imported into the Odeon simulation program.

For the Boston Symphony Hall, Aural-Environments already had access to a completed Odeon simulation model [1]. Also available were independently measured on-site acoustical data for confirming the accuracy of the simulation program and room model [2].

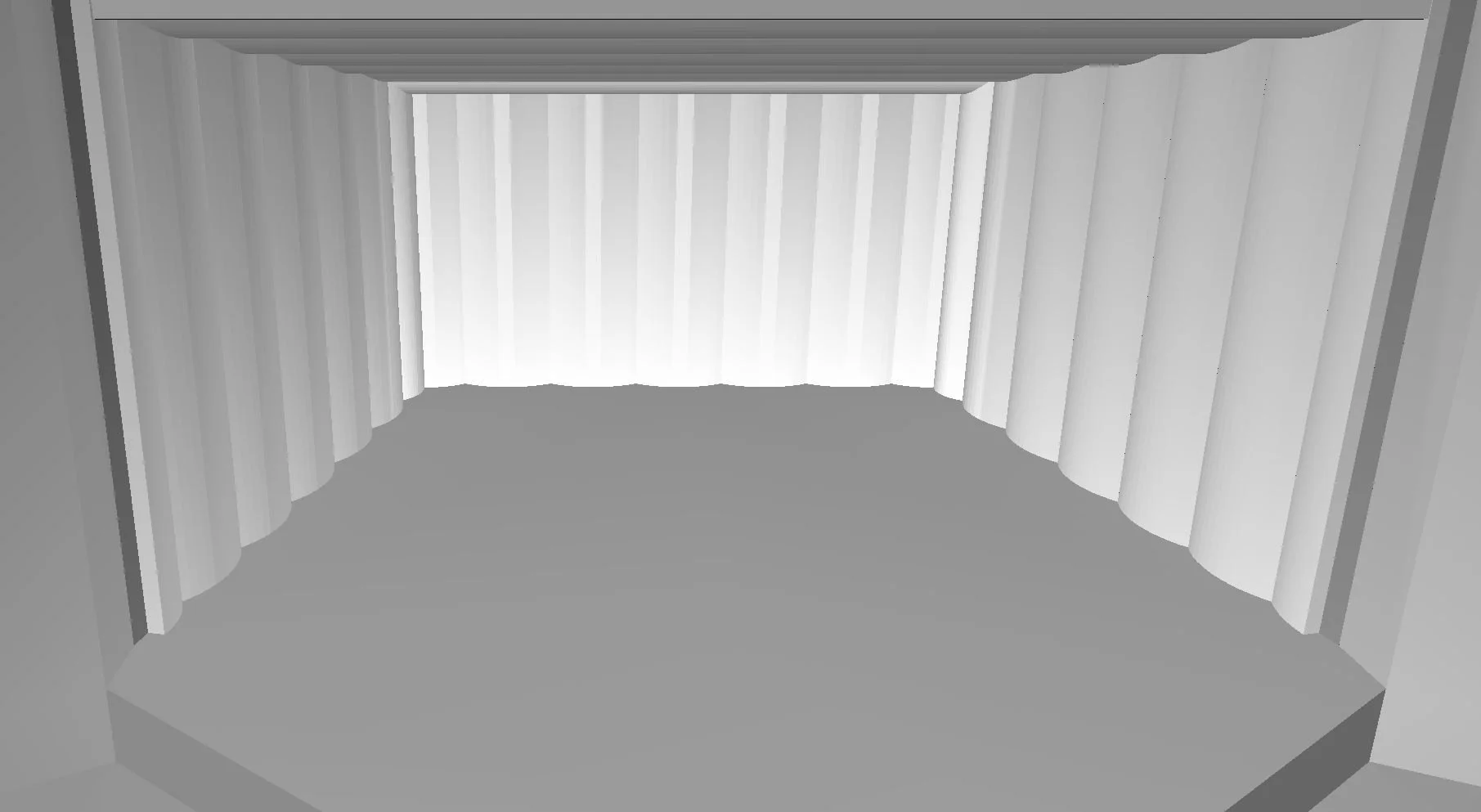

The Van Wezel was particularly interesting. The modeling approach treated this multipurpose hall as two coupled spaces: (1) the stage with its orchestral shell, and (2) the audience volume. Based upon listening to live instruments projecting from stage into the audience, as well as speech projecting directly from the Van Wezel’s PA speakers into the audience, this approach seemed warranted. Indeed, PA sound quality confirms the audience space to be acoustically quite dead, with orchestral sound dominated by the stage’s acoustics. Consequently, the stage-shell model would be quite detailed, while the surface and absorption model of the audience area could be simplified. In forming this two-part digital model the publicly available Van Wezel Assets document was very useful [3], these drawings sufficient for production of the detailed stage-shell surface model, pictured above. An outstanding task is checking this interim model against on-site acoustical measurements.

The goal being to experience at the listener’s location the immersive sounds corresponding to one or more instruments up on stage, the next step is to define audience listening locations and stage instrument locations, and then generate with the Odeon simulation tool the complete hall acoustical response between these two locations. Finally, the simulation program utilizes instrument sound recordings of individual musicians performing in a “acoustically dry” room, to produce the immersive instrumental sounds at the listener location. For the Listen experiences linked below, these raw instrument sounds were recorded at the Technical University of Denmark [4], though it would be relatively easy to substitute recordings of Sarasota Orchestra musicians.

As a calibration check between Van Wezel and Boston models, test simulations were performed and loudness levels compared for: a) first arriving direct sound and b) total loudness level, including direct and early reflections and room reverberation. With identical musician-listener distances, direct path loudnesses matched. However, for total response Boston was found to be louder by 2.5 decibels, very significant for this important acoustical parameter, the result of Boston’s substantially longer reverberation time plus its higher density of early reflections. This is apparent in the individual instrumental and orchestral comparisons in the Listen section below.

[1] Odeon concert hall models, release version 16: https://odeon.dk/examples/concert-halls-and-theatres/

[2] Boston Symphony Hall acoustical properties: Beranek, L. Concert Halls and Opera Houses, second edition, Springer, pp. 47-50, p. 619.

[3] Van Wezel drawing references: https://www.vanwezel.org/assets/doc/VWPAHTechPackJan202525011092847-ca92123976.pdf

[4] Derived from anechoic symphony orchestra recordings at the Technical University of Denmark and licensed from Odeon A/S.